What happens when artists venture off the beaten track?

1 Nov 2022

David Whetstone spoke to five contributors to Hinterlands, Baltic’s exhibition offering a sideways view of our North East landscape

A fragment of ancient woodland on an industrial estate, a brownfield site where willows grew wonky, an upland bog… all feature in an autumn exhibition at Baltic.

They might not sound like places you’d want to linger but in each case an artist did.

The results can be seen in Hinterlands which, as the name suggests, focuses on places away from our famous coastal or riverside beauty spots.

They’re places where nature and industry have rubbed along, often for centuries.

And anyone tempted to deem them worthless should see the exhibition.

Michele Allen’s contribution is a multi-media declaration of love.

You can see it in the photos, the ‘nature table’ exhibits, the film shot across seasons with a soundtrack of birdsong and traffic, and even the notice of a pending tree preservation order, proudly displayed.

Basically, all the work centres on a pocket of ancient woodland in the middle of an industrial estate, says Michele.

“It’s in Gateshead and it’s tiny.

She found it in 2015 while researching colliery wagonways. The vegetation hinted at a rare pre-industrial survivor.

“I had a sense of it being a fixed point in space or time, around which the world had changed dramatically. I imagined it having witnessed coal running past for 300 years.

“People walk through it and enjoy it as a natural space but it wasn’t protected.”

Having decided to film it over a year, she heard of plans to chop down trees and contacted the council. They sent an ecologist who designated it a local wildlife site.

The preservation order came too late for two old trees and Michele spent days sanding smooth a chopped fragment as a memorial.

“It was a slightly cathartic process. I was so upset about it.”

Michele says her efforts were less about trying to encourage more public use of the wood than to open a discourse.

“A lot of the work I make is about site and place and the layers of understanding we bring to them.

“They have a physical reality but how we think about them is often shaped by how we think about landscape artistically or culturally.”

Her project’s title, The Weight of Ants in the World, came from a book she read to her son which suggested all the world’s ants together would outweigh us.

She had found comfort in the idea we’re not as dominant as we imagine ourselves to be. Sadly, it turned out to be more urban myth than gospel truth.

“But I liked it as a title because what I’ve been trying to do here is bring out the mass of the place, the density and age of it and the life it’s seen and keeps on seeing.”

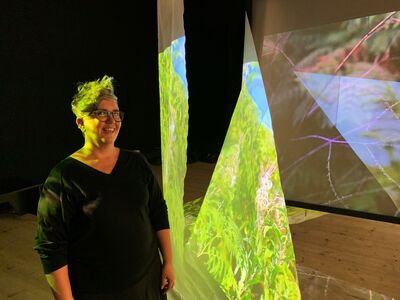

Another who stumbled on a bit of hinterland nature is Dawn Felicia Knox whose hypnotically overlapping film installation, The Felling, is displayed nearby.

She recalls the “really gorgeous” clump of trees she found in Felling, Gateshead, where she once lived.

But because of old pit workings underneath they were unstable. They’d grow at wild angles and when they fell over the roots would be clenched like fists.

Among the roots she’d see colliery spoil and once she found a fossil.

Appointed artist-in-residence at the Lit & Phil 10 years ago, she used the opportunity to research the site.

She learned about the Felling pit disaster of 1812, when 92 miners died, and did a project about fossils and plants on the site, working with archaeologists and geologists.

She learned how toxins in soil can be a dating mechanism, layers of heavy metals, asbestos and plastics reflecting damage wrought by successive industries.

“This,” she says, “is our legacy as humans.”

Returning after a decade to work on her Hinterlands commission, she found a brownfield site, trees gone but development thwarted by contamination.

“If I lived on there I wouldn’t be healthy,” she says.

Plants seem to have adapted, though, albeit not in a way humans can derive comfort from. Analysis shows how they draw harmful materials like cadmium, nickel and lead up from the soil.

For her Baltic piece, Dawn worked with Newcastle-based Star and Shadow and sound artist Anastasia Clarke whose accompanying soundtrack was made using data relating to this process.

Dawn, an American, met her partner, who is from the North East, while travelling in Mexico.

“I came for a month 17 years ago and I’m still here. My oldest has just turned 15. This is about trying to learn about the place I found myself, its culture and heritage.”

Brushing aside the suggestion she might prefer to be a botanist or geologist, she says: “No, I feel privileged to be an artist.

“We can be glorious magpies, picking up bits we like and seeing how things overlap in ways that being dedicated to one discipline perhaps wouldn’t allow.

“We can cross-pollinate lots of ideas.”

Another lorious magpies’ is Anne Vibeke Mou, long resident in the North East but originally from Denmark.

An interest in glass and botany is reflected in her delicate pieces; and they’re not unrelated interests, says Anne, plant ash having been used in traditional glassmaking.

She explains how an interest in the history of lead glass was sparked by taking a studio above old lead mine workings in the North Pennines.

“Lead was used in the glass industry in a big way but it’s incredibly toxic.

I do sometimes make glass from scratch but making lead glass is not something you want to do in your studio.

“What I did for this was collect pieces of vintage lead crystal that had been damaged, break them down, heat them in an electric kiln and re-shape them.”

She reckons these bric-a-brac shop and eBay acquisitions probably contain lead mined in the North Pennines.

Now they are reborn as elegant cornucopia, resembling the mythical horns of plenty and the Golden Horns of Gallehus, Danish treasures famous for having been stolen and melted down.

Look closely and you’ll see Anne has engraved them with tiny plants - moonwort, miniature ferns that grow in the area around her studio.

“I chose them because of their mythology. Alchemists believed they could help turn lead into silver or gold,” she says.

These magical plants are well hidden and only after much fruitless crawling around and a chance encounter did Anne find some.

“Moonwort? Yes, come with me,” instructed the elderly lady she met on the fell, and strode off with Anne in pursuit.

This, it transpired, was renowned botanist Dr Margaret Bradshaw, still engaged in fieldwork in Upper Teesdale in her mid-90s.

Jo Coupe stands in her little thicket of… what exactly?

Playful props for a Teletubbies-style TV show? The growling and crackling soundscape gives the lie to that.

Hush hush scientific monitoring equipment? Mmm… with rainbow umbrellas? Perhaps not.

“They’re home-made sound-recording devices,” explains Jo.

They’re my version of what sound artists use to record birdsong and things from a distance. I was using them to record the sound of pylon crackle.

“I’ve been interested in this for ages because there was a pylon line going through the village where I lived.”

She was intrigued by the pylons’ physicality – “hugely visible structure that we somehow don’t see” – and their persistent, unsettling sound, reminiscent to her of lions she once heard roaring in a zoo.

“There was a visceral terror attached to that sound and somehow pylon crackling has something of it too, a deep bass that’s hard to locate.

“I wondered, if you could bottle it and take it out of context, what might that feel like?”

Here’s the answer, a sci fi rumbling infused with occasional bird and traffic noises which her devices also picked up in Chopwell Woods.

And because she’s a sculptor, the home-made devices with their umbrellas and lampshades (one prototype involved a wok) are crucial to an installation meant to reflect that countryside through which pylons and dog walkers stride.

It’s called After the Rain because, says Jo, sounds are louder after a downpour. The appropriateness of umbrellas only struck her later, she admits with a smile.

Next door, meanwhile, people are watching other people in waterproofs getting a proper drenching.

This is Fieldworking, Laura Harrington’s film recalling the time she invited a group of people to camp at Moor House: Upper Teesdale National Nature Reserve.

Another art world magpie, Laura has been drawing inspiration from this ecologically important expanse of blanket bog for 10 years. What would fieldwork conducted by this disparate group look like?

They were six artists from different disciplines, two film-makers and an ecologist. It was, Laura has written, “a space to think about how artists and landscape meet and what happens in that encounter”.

The film, nearly finished when Covid hit, has no commentary.

“It isn’t meant to be a documentary of what happened,” says Laura.

It’s more like the end bits of an Attenborough film.

“It was about bringing people to Moor House, learning more about it and sharing it with others and sharing methods.

“There was this idea that looking at the interaction between the artists and the landscape might reveal more about it and I know it has influenced how the others have thought about things.”

She smiles a little ruefully. “We couldn’t know we’d be drenched the whole time. There was a lot of water going on.”

You might feel grateful to be sharing the experience second hand in this rich and thought-provoking exhibition.

Hinterlands also features work by Emily Hesse, Foundation Press, Alexandra Hughes, Uma Breakdown, Mani Kambo, Sabina Sallis and Sheree Angela Matthews.

It’s on Level 3 at Baltic until April 30, 2023.